Anaerobic Digestion Biomass is a largely unused resource, and as this article shows, by using the example of unused verge clippings, the energy potential is far larger than is appreciated. Read on to find out how waste biomass, if fully developed in the UK and globally, can become a huge source of energy, fertilizer, and fibrous material.

When the anaerobic digestion process is used, it not only produces biogas energy the byproduct output (known as digestate), is not only a soil improver and fertiliser but can also be used to make building materials, bedding material for cattle, etc.

Researching available biomass feedstocks to use as Anaerobic Digestion Biomass is the starting point for designing all anaerobic digestion plants.

Researching available biomass feedstocks to use as Anaerobic Digestion Biomass is the starting point for designing all anaerobic digestion plants.

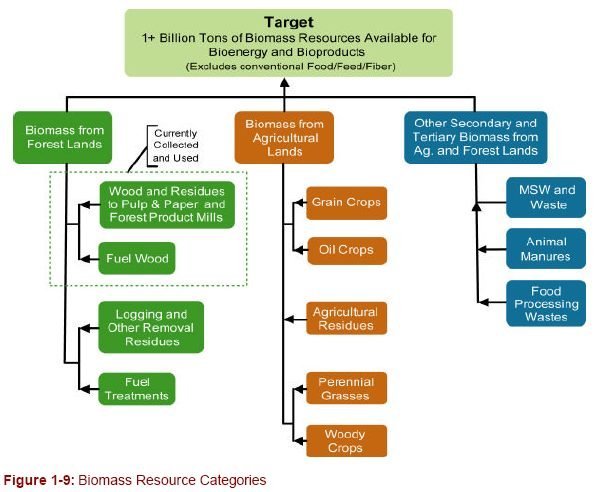

At this point, it is useful to make the point that there are far more categories of biomass that are suitable for use as an anaerobic digestion biomass feedstock than just the traditional textbooks would have you believe.

An idea of the huge scope of the available categories of suitable anaerobic digestion biomass can be seen below.

The following table of biomass resource categories is taken from a US report entitled, “Biomass As Feedstock For A Bioenergy and Bioproducts Industry: The Technical Feasibility Of A Billion-Ton Annual Supply”. It lists a wide variety of untapped biomass sources, not including the crop wastes that are just starting to be digested, in the following categories:

- Biomass from Forests

- Biomass from agriculture

- Other secondary and tertiary biomass sources.

The mass of the above-combined biomass sources in the United States would be over a billion tons annually. That could be powering a far larger biogas industry than exists today, with all the climate change mitigating consequences so much needed to limit climate change.

In this article, we use the example of the currently unused biomass available in the UK if verge trimmings

From that graphic above, you will see that biomass is a largely untapped resource with a great deal of potential for the future development of anaerobic digestion.

The Scale of the UK Anaerobic Digestion Biomass Resource is Being Underestimated and Wasted

According to the Anaerobic Digestion and Bioresources Association (ADBA), during their world Biogas Expo in July 2017, there were 10 million metric tons of food waste and 90 million tonnes of manure produced in the UK each year.

Yet anaerobic digestion plants only use 2.4 million tonnes of food waste and approximately 2 million tonnes of manure.

Perhaps the best way to demonstrate that there is a vast untapped resource is to provide just one example, and to do that, it is not necessary to look very far at all. This resource will be at the end of the front driveways of homes. Many people are reading it now. What is it? It's grass verges…

“UK Grass Verge Cuttings – If Collected Nationwide Would Provide an Extra Grassland Area the Size of Essex”

Imagine the huge additional biomass bioresource that the nation's road verges would provide if all were mown and the cuttings were collected and digested.

Lincolnshire County Council is the leader in the UK for verge grass-cutting collection. Agriculture in Lincolnshire is highly intensive, and that means that the species of the once diverse grasslands are under heavy pressure of extinction.

For many species in large areas of the county, these original local plants are only to be found in grass verges that are mown after the seeds have set each year, with the cuttings removed. Unlike some European countries, cuttings removal is not a legal requirement when the Council cuts the verges.

Unfortunately, cutting has been curtailed due to austerity funding post-2007 and the banking crisis. The result of local government funding reductions is less frequently mown verges and rank growth. The result of this is that the cut mowings tend to compost themselves in place, and that raises the fertility of the verges. Rank growth follows, and that threatens the delicate grassland species with the result that they are being squeezed out.

The Council has been looking at new ways to fund grass-cutting to protect the ancient local grassland species without placing the burden on ratepayers. They anticipate that using their verge cuttings as an anaerobic digestion biomass feedstock will enable a neighbourhood network of biogas plant operators to pay for the preservation of the area's native grass flora and fauna.

The Council's work to bring about species preservation through grass mowing collection and delivery to anaerobic digestion plants is illustrated in the following article excerpt, originally published on the BBC's website:

Lincolnshire Grass Cuttings Used to Produce Electricity

Lincolnshire County Council is using a special machine to cut and collect grass cuttings, ready for anaerobic digestion. Delegates from councils across the country have been to see how this pilot scheme works. The scheme is monitoring biogas yields, biodiversity impacts, and the costs of harvesting grass in this way.

The cuttings are taken to a biomass plant at Scrivelsby, near Horncastle, and used as fuel.

Ultimately, if the pilot scheme is successful, the council could get up to 10 of these machines. The council has about 4,000 miles of grass verge to maintain.

Dr Nick Cheffins, who helps oversee the trial, said:

“It could be a renewable power source. We sell electricity to the grid and use the heat also produced for various agricultural processes”.

The scheme was looking to get enough data to produce a “toolkit” for other interested councils, he added.

The grass is collected to eventually produce electricity. Through anaerobic digestion, which is a process by which microorganisms break down biodegradable material in the absence of oxygen.

Organic material such as manure, crops, grass, or slurry is put into large containers. Once this material breaks down, it produces biogas such as methane. The methane can be converted and fed into the National Grid.

Councillor Richard Davies said:

“This is a first for a local authority. It's early days, but we think it's worth testing it out in the real world.”

Mr Davies said removing the cuttings from the verges helped to protect wildflower growth and slow down the rate of grass growth.

“It makes sense from both an environmental and economic point of view”, he said.

Mark Schofield of Lincolnshire Wildlife Trust said the scheme could:

“throw a lifeline to grass land” and change the way grass verges were managed.”

The scheme is being run with support from the Lincolnshire Wildlife Trust and Leeds University. … via Grass cuttings used to produce electricity

Peakhill Associates Ltd. delivered the above study on the “Utilization of Anaerobic Digestion to Sustain the Harvesting of Road Verge Biomass” on behalf of Lincolnshire County Council (LCC). For more information on the study visit Peakhill Associates here.

Is Your Company Sitting on a Hidden Asset of Suitable Anaerobic Digestion Biomass?

Many companies possess suitable anaerobic digestion biomass, which is a hidden asset they are unaware of, and have yet to carry out even the most basic reviews of their company's product and waste streams as they exist currently.

If those companies were to re-assess what they are now very often treating in industrial effluent treatment plants, at very significant expense, it could become an income stream using their own free biomass feedstock if they were to invest in a plant to produce biogas.

To highlight the opportunities that companies that currently produce a lot of waste biomass, often called “high BOD (or COD) industrial effluent,” such as those in the food processing industry, generate, we have produced our video ourselves.

We have embedded that video below. If your company is one such company that treats your valuable biomass as waste and does not digest it, we suggest that you watch the video below:

[Article published 3 November 2017.][Updated March 2024.]

Please tell us where we can read the report you mention, called “Biomass As Feedstock For A Bioenergy And Bioproducts Industry: The Technical Feasibility Of A Billion-Ton Annual Supply”. The claim of a billion plus tons of this biomass being available is remarkable. Just what material is this and where is it?

Consider writing, next time, about digestate dryers. A Digestate Dryer connects to an Anaerobic Digester using CHP technology to dry the waste product at the end of the digestion process. It will produce a dry pellet which is a more concentrated fertiliser. It utilities the surplus heat from the CHP, benefits from RHI and reduces transport costs and improves transportability’s the end result is much smaller in volume. We are Brightestfuels.

Biomass combustion technologies can be employed to generate electricity by using the combustion heat to raise steam and drive a turbine and generator. This is a similar process to traditional fossil fuelled electricity generating plant. You can continue to ignore Trump and others. Climate change is not evident, but if you must – just burn biomass.

Loved your writing. My question is. What about the top-of-tree biomass created during logging? Can that be collected and used as an anaerobic digestion feedstock? I guess the moisture content is too high in the UK for that material to be used as a boiler fuel?

Yes. Top of tree biomass can be used as an anaerobic digestion feedstock.

If this is the truth. I’m genuinely impressed by Lincolnshire County Council’s approach to verge grass-cutting collection, and frankly, I think this should be a standard practice everywhere, not just an exceptional case in the UK. The intensive agriculture in Lincolnshire, has put immense pressure on local biodiversity, threatening numerous species with extinction. It’s a bleak scenario that underscores the urgent need for sustainable agricultural and land management practices.

The fact that these grass verges serve as the last refuges for original local plant species highlights a broader environmental issue. It’s astonishing and somewhat tragic that the survival of these species hinges on such a narrow margin—literally the edges of fields and roads. The practice of mowing after seed set and removing cuttings, though not mandated by law, is a brilliant conservation strategy. It not only helps in seed dispersal but also prevents nutrient overload, which could further favor aggressive, fast-growing species over the native flora.

It’s baffling to me why such practices aren’t legally required, especially considering the clear benefits for biodiversity conservation.

I also must say that developers from now on have to submit statements for planning that show that the project will raise biodiversity. How can it be right on the one hand for councils to be allowed not to mow verges and damage diversity when developers are being restrained from building houses because they must spend on biodiversity?